September used to mean a new school year, new beginnings. Now it means 9/11 and its ghosts. I’m one of them, I suppose, because I was at work that day, across the street, and even though I didn’t die, I did. This year, I didn’t mark the 9/11 anniversary, for the first time. We’d been packing up our eldest to send off to college and then moving six days later, so I didn’t have the time or the opportunity to reflect. I’m making up for it now.

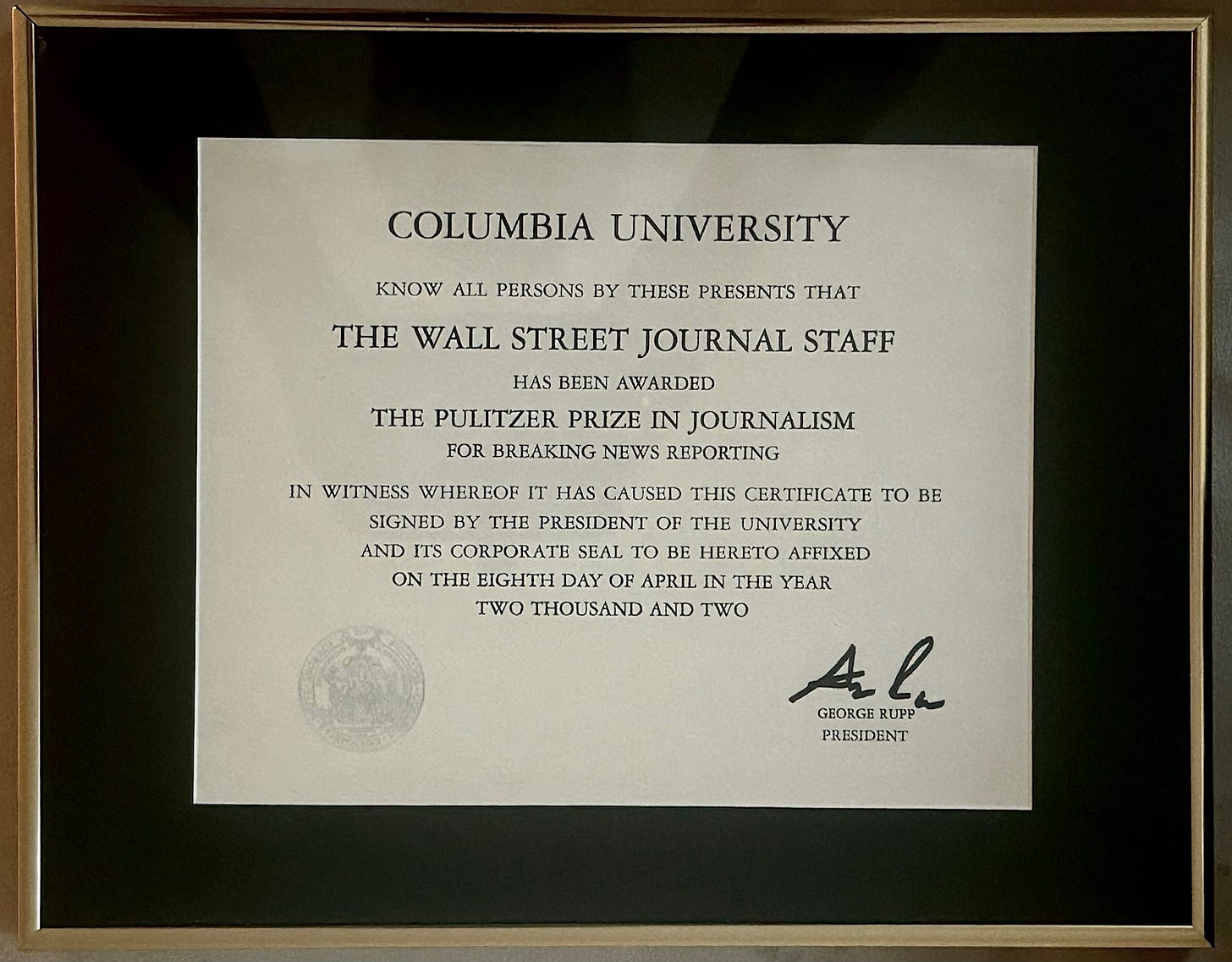

What’s coming to mind is an old phrase from the ‘60s. You’ve probably heard it: The personal is the political. That a personal experience can be traced to one’s location within a system of power relationships came alive for me on 9/11. I went to work one morning in a Donna Karan jacket and witnessed a geopolitical cataclysm playing out 60 feet away and about 1,368 feet up. The attacks netted me PTSD, thyroid cancer and a Pulitzer Prize, all in a few hours. In the aftermath, the U.S. lost its mind in its thirst for vengeance, transforming into something unrecognizable. The new America that 9/11 wrought was sick and violent, so I eventually made the painful decision to leave home.

Below is an excerpt from an account of that day that I wrote in 2006. My literary agent at the time praised my work, but said it was unsaleable because the market was saturated with 9/11 writing. Her suggestion? We should wait for the next terrorist blitz, after which we could repackage this material. You know, she said. As a reflection from ‘the time between the attacks.’ A second attack on New York has not yet occurred, thank God. So many marketing opportunities lost! I’m sharing this with you, instead.

September 11th split my life in two.

There was a before and then there came a long after, during which I realized I had become a victim of terror, even though I didn’t want to be. I resisted the concept for a long time. I fought it hard and I lost. They win. My brain is smoked now and I can’t concentrate. I don’t have the same sense of fight that drove me for most of my life. Everything now is personal and most of it hurts.

September 11th demarcates my life. It split in half my sense of time, but also my sense of hope. If you’re not safe, you don’t hope. You act. I’ve been on overdrive ever since that day and I don’t understand anyone who isn’t.

Before 9/11, I don’t think I would have said that safety was particularly important to me. I knew it was a bad world. I’d spent years in international journalism and I’d been to some bad places. I’d edited thousands of stories about dark happenings and tragic outcomes and I was sensitive to the stories. I remember reading the New York Times’ coverage of the 1989 Tiananmen Square massacre with tears running down my face. I was shocked and outraged that those students had died a bloody death for their political ideals. At the time, I felt I was with them in spirit—my empathy was in full bloom – but now I know I cried for them from across an immense gulf. It wasn’t the 7,000-odd miles of space between New York City and Beijing, but the infinitely larger gulf of probability. I knew that my government wasn’t going to shoot me for peaceful protest. No one was going to kill me for any political reason at all.

I believed this up to and until 8:46 a.m. on September 11th, 2001.

I was American. We don’t believe in death. We believe in power and we believe in dollars and we believe they are very often the same thing. Death by political violence didn’t happen to us because we had a bad-ass passport and lots of money. We had the Pacific on one side and the Atlantic on the other. We had Canada and Mexico leashed and tied to a post. No one could get anywhere near us, I believed.

I lived in New York. It was a global city, a cosmopolitan city. It was the city that never sleeps. It was really crowded and with that many people in that small a space, I’d always felt confident that someone somewhere must be paying attention to security issues. New York had national treasures. It had the Statue of Liberty and the New York Stock Exchange and since nobody had ever blown them up with plastic explosives, I assumed it was because they’d been deterred. I didn’t think the reason we had been safe was simply because no one had ever tried to hurt us.

I assumed that New York had master plans and policies and procedures that would prevent bad guys from blowing up buildings. Surely, New York had spies with eyes on its payroll. If you had asked me on September 10th if I felt safe there, I would have said that I did. Yes, I would have said. I don’t like crowds and I hate the subway, but yes.

Nineteen months later, I was sealing the windows of my Brooklyn condo with duct tape against the nerve gas attack Saddam Hussein was supposed to launch in response to the imminent U.S. invasion. I had quit my job, because if I was going to die at work, I wanted to get paid more. I was sitting at home, chain smoking at 4:00 in the morning. I always had a pot of coffee on and I could never finish or start anything because of my damn nerves. I didn’t know what the hell had happened to me.

I never slept.

I saw other people only occasionally and it was an effort. Every time a car backfired, I would freeze in fear. I scrolled the news constantly. I was no longer able to conceive of a future, which is a hallmark of PTSD.

I didn’t know it at the time, but I was waiting to die.

The scale of 9/11 was vast. Or more precisely, it was vast to me.

Certainly, there have been bigger disasters, natural and otherwise. The physical destruction totalled a few square miles, and the bulk of that was vertical. The death toll was heartbreaking, but to count 3,000 dead after an air attack on New York City seems positively lucky compared to what might have been. The first estimates, early that afternoon, were 50,000 dead or more. “Whatever the number is, it will be more than we can bear,” Mayor Guiliani famously said, and it was true.

September 11th was vast to me because it happened on so many levels simultaneously. It happened to the world, but it happened to me, too. It happened to my limbic system, my hippocampus and my fear-primed, screwed-up amygdala.

It happened to the people who were with me on the R train that morning, pulling into the Chambers Street stop at around 7:50 a.m. Some of them emerged from the station and walked right toward the World Trade Center. I walked left to One World Financial Plaza. One of the thoughts that returned to me often in the months after the attacks was whether anyone on that subway car with me died. For a long time, I entertained the crazy idea that I should have known the ones who were marked and saved them somehow.

It happened to my fellow New Yorkers. I saw them dying. I saw a man in a red tie jump from the North Tower and then try to navigate his fall with his arms. I saw him try to live. I saw the instrument of some of those deaths, the second plane passing like a shadow on the edge of my field of vision as the paper fluttered so beautifully, a spiraling stream of flashes of white, floating downward on the superheated air.

It happened to my colleagues, some 30 editors on the Wall Street Journal’s Overseas Copy Desk. Some of them were my friends, and some of them very quickly turned symptomatic, as we came to call it. I’ve never seen so many people change so much so quickly.

It happened to my office, which we evacuated at 9:13 a.m., some of us never to return. It was partially destroyed by the towers’ collapse and as of that afternoon, my job relocated more than 50 miles away, to South Brunswick, New Jersey.

It happened to my World Trade Center, my Wall Street, my Lower Manhattan.

It happened to my New York, where I’ve lived on and off since I was three years old. I’ve lived all over the world, but New York is where I go when I go home.

It happened to my country.

It happened to my newborn century.

It happened to my world.

I was there that day, at my desk across Liberty Street. What does that make me? A bystander? A witness? Lucky? Unlucky?

I came around only very slowly to the idea of myself as a victim. What I mean by that word is not that I am helpless, because I am not, but that I was scarred by that morning, and changed by it. At dawn on the morning of September 12, I was standing in my mother’s bathrobe on the roof of her apartment building in Brooklyn Heights, holding a cup of coffee I couldn’t drink because of the nauseating stench of jet fuel steeping the still-burning rubble of the World Trade Center directly across the East River. In a city of more than eight million, there was hardly a sound except the chirping of birds as they greeted the sun and the engines of two F-14 fighter jets circling Manhattan above the drifting smoke. The only other thing moving was the Staten Island Ferry, which was said to be transporting corpses from what we were already calling Ground Zero.

The world as I had known it was gone. But I would have dismissed as ludicrous the idea of myself as a victim. I was alive, for one thing. For another, no one I knew well had been killed, which seemed very near miraculous. And last, I didn’t have a bump or a scrape or a bruise, just a slight cough and a sore patch on my left forearm that was hot to the touch. The victims were those who died, those who were hurt, and those who loved them. I was one of hundreds of thousands of people on the periphery of the tragic action who escaped without a scratch. In a sense, I am no different from anyone who was in New York City that day and saw the towers burn and collapse. In another sense, I’m a casualty. Officially, my status is as an innocent. I have a letter from the New York State Crime Victims Board declaring me to be so, the first step in my bid for survivors’ benefits.

FEMA defined a victim as anyone who was within a ten-block radius of the towers that day. That’s every single one of my colleagues. That’s the 15,000 people estimated to have evacuated the towers. That’s all of Battery Park City, a huge chunk of lower Broadway, most of Wall Street. That’s me. I don’t know how much stock I put in FEMA’s designations, but I do know this: If there are degrees of victimhood, closer was worse. The angriest I felt on September 11th wasn’t during the attacks themselves, but afterward, when I saw people sitting at outdoor cafes and, over scampi, watching as the ashes of the dead rose to the sky.

Eighteen months after the attacks, I moved out of the city to a sleepy backwater in Columbia County, largely because I was crippled by fear of a reprise. Getting on the subway cost me a day of worry on either side, as well as heart palpitations and trouble breathing. I was a pitiful thing to behold and in the end, it just wasn’t worth it to go anywhere. My husband said this was no way to live, so we moved away from the scene of the crime, but I didn’t put it behind me. Two years, three years later, four years later, I still kept the countoff running. I measured time and everything else from 8:46 a.m. on September 11, 2001. Many people also moved out of the city, but more stayed put in New York and seemed to have gotten over it. I didn’t understand that and I still don’t. I don’t understand getting over it.

Every year on that day, my friends and family call to pay their respects, as if I really had died but was still somehow there to accept their well wishes. On the third anniversary, someone said, “I think we’ve all succeeded in putting it all behind us.” This was a New Yorker, someone who wasn’t prone overmuch to introspection and who certainly wasn’t downtown that day.

Not even hardly, I thought.

When those people I saw jumping from the towers or splattered on the pavement rise from the dead and tell me they’ve put it all behind them, then I will be at peace. Until then, someone has to remember and it seems to be me. The shrink said that in the aftermath of trauma, people revert to whatever their early stance was. Apparently, mine was vigilance. I have been the silent sentinel of New York City for five years now. I’ve been waiting all this time.

The attack happened to the world but it also happened to me, and in a way that could only show itself with the passage of time. Some people have said that I have no right to write about 9/11 because I have a heartbeat, and no scars or lost loved ones. I was a mere voyeur that morning, and an imposter afterward. So be it. The events of that day are sacred in American life the way nothing else I can think of is and the farthest thing from my intention is to profane its memory.

But I have a right to write about it because I paid for it.

I did not call my family when I got to my mother’s apartment that day because it didn’t occur to me that they would know what happened, any more than if I’d twisted an ankle. It happened to me. It was an event in my private world.

It was personal.

I didn’t call anyone until noon. My family suffered until then and I will never forgive myself for that. I’d been a newspaper editor for years. I’d been a wire reporter for a long time before that, trained to call in breaking news. Yet it didn’t occur to me that my family would know that three hours ago, across the street from my office, two planes had slammed into the World Trade Center, creating an inferno that incinerated thousands of people alive, collapsed the towers and buried lower Manhattan in a cloud of toxic dust that for a moment blotted out the sun.

Notes from Exile wants liberty and justice for all. So share this post with your friends!

@Laura Skov - What phenomenal evocative writing! It sounds like you wrote this five years later. How do you feel now, since several lifetimes seems to have happened since then? At the time I couldn't read anything, and now I'm overwhelmed by stuff rolling in every five minutes, and I think you decided to bug out - haven't gotten to that part. But,I've discovered I have an ugly fascination with the jumpers - and modulating that black fascination with a need to stay connected to my humanity. And, it seems to me you capture enough of the specificity to reward my black heart (something about the beauty of the floating papers), and my need for my humanity (wondering if you're a survivor because you were only next door). I will keep reading. I don't know about others, but as a resident neighbor at the time of the Los Angeles International Airport, we could see in real time the defense of the nation. All air traffic into and out of LAX halted, and it was weird to have empty skies. And then the periphery of LAX became filled with patrolling police helicopters and any other protective units that had their own helicopters constantly patrolling, because we didn't know "What else?" "What next?"

I will try to read all you have available on your thoughts about 9/11. How long have you been away? For 6 years I've been begging my husband to move, but we no longer have the financial appeal to move to New Zealand, where I fortuitously have a cousin and his family. All my grandparents escaped the pogroms of Europe to America around 1910, escaping the horrors to come. And now, I wished I had asked them more about it. They came with their smarts and work ethic, a knowledge of five languages, English not being one of them, and surviving to raise successful American children - at least 3 generations of descendants now - maybe four. And here I am thinking about following in my grandparents worn boots. Friends are applying for dual citizenships if they can prove their descendant came from that country. Several to Italy, one to Germany, another one I forget where. And if I could prove - which I doubt - I could apply to Russia, Poland, Lithuania, and Ukraine. Somehow those all hold less appeal than Italy. And of course for Jews (me) I could go to israel. Which is having a hard time of it. So - I guess I'm stuck. Better to fight it out at home.

Oh how the world was changed. Thank you for writing this.

Good luck with college drop offs & moves!