"I am, somehow, less interested in the weight and convolutions of Einstein's brain than in the near certainty that people of equal talent have lived and died in cotton fields and sweatshops.” – Stephen Jay Gould, The Panda's Thumb.

Since I watched the 2013 documentary Finding Vivian Maier the other night, I’ve been haunted. I keep thinking of what might have been, for her and for all of us.

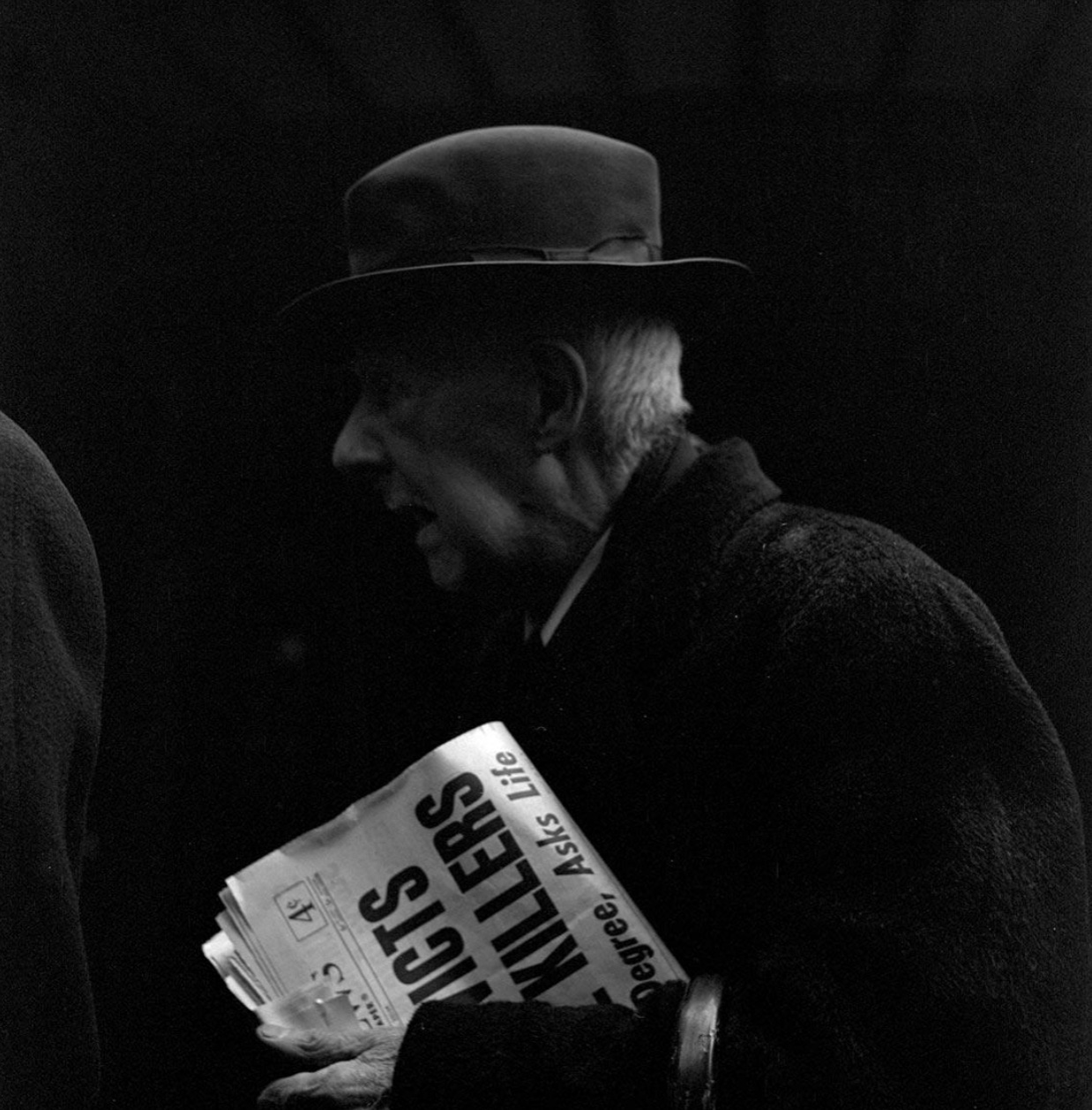

Vivian Maier (1926-2009) was a brilliant American photographer who made her living as a nanny, mostly around Chicago. She was eccentric, to put it mildly. She was rigid with rules and routines. She dressed oddly. She claimed to be French but was born in New York City. Her weirdly Germanic French accent was suspected by some to be fake. She never married and had no children. She was a hoarder. She appears to have badly mistreated at least one of her charges. She did not like to be touched and preferred to be outside, moving around.

So she did. Night and day, with her charges or on her own, she compulsively walked the streets, shooting film on her Rolleiflex camera. For reasons unknown, she never promoted her work, so no one knew her name during her lifetime. She herself didn’t see much of her own work, because she died with more than 100,000 undeveloped shots boxed up in a storage locker. If the right guy, filmmaker John Maloof, hadn’t bid on her locker, she probably would have remained forever unknown.

Why didn’t she develop all that film? Why didn’t she exhibit? Some people are constitutionally unable to sell themselves and maybe she was one of them. It’s asking a lot for someone as talented as she was in one area, photography, to also be good at selling. It’s probably asking too much. Maybe she had no interest in pursuing the commercial side of art – only the work itself mattered. She fiercely guarded her own privacy, so maybe the experience of exhibiting her work would have felt to her like an intrusion. In any event, we’ll never know. But I think she was too tired from all those kids.

Anyone good enough to shoot those images was good enough to perceive their brilliance. In my mind, it’s inconceivable she didn’t know how good she was. She knew and yet she did nothing to get her work out into the world. Too poor to pay the fees for her storage locker, she was rescued from homelessness only by her former charges, who took over her rent. She died in obscurity.

In America, artists have to have a 9-to-5. As a result, too many artists have to waste their time and energy on bullshit. They probably do this work a little half-heartedly, which has a cost for the rest of us. Do you want a depressed artist fixing the brakes on your car? They are probably resentful as they walk dogs, pump gas and bag groceries. They probably wait for the end of their shift, when they hope to do their art with what remaining energy they have. It can’t be much.

I think this is stupid of capitalism. It’s shortsighted to ignore talent and callings the way we do, not least because that’s where genius is. It’s dumb to see labor as meat for capital instead of as people with fantastic brains. Great Americans have had to work silly day jobs, resulting in an immeasurable cultural loss. We pay for day jobs with uncreated art. We should care about that.

I respect all work, but come on. Wallace Stephens won the Pulitzer Prize for poetry, but he also worked at the Hartford Accident and Indemnity Company for 40 years. Can you imagine how bored he must have been, poring over indemnification clauses? Herman Melville, the mind that produced Moby Dick, worked as a customs inspector for New York City for 19 years. And Kurt Vonnegut managed a Saab dealership in Cape Cod for a while. In the face of these facts, I don’t admire these artists’ pluck in finding a way to put food on the table. I find it tragic that society didn’t prize them. The day job represents a waste of creative talent that cannot ever be recovered.

It’s not just an American thing, of course. I don’t say this very often, but Europe doesn’t do this one much better. Charlotte Brontë was a governess, earning a pittance for exhausting work. Paul Cezanne was a successful stockbroker until he quit to pursue his art, whereupon Madame Cezanne took off. But other European artists found a way out of the day job trap: Patronage. That tradition could light a path forward.

Picasso didn’t have to flip burgers. He could devote himself full time to his art because he found in Gertrude Stein a patron with deep pockets. That’s the reason we have Guernica. Michelangelo had the patronage of the Medici family of Florence, as well as Pope Julius II. This is how you get a Sistine Chapel ceiling and the David. Leonardo da Vinci was also supported by the Medicis, as well as by the Duke of Milan and King Francis I in France. This is how you get a Mona Lisa.

But how do you get a Vivian Maier?

There are two ways to see her story. You could say that she triumphed because she accomplished the work. As a nanny, she could keep herself fed and housed, finance her passion (obsession, really) and live the way she liked, outside and moving around. She found a way to create the art for five decades. But you could also say that her life was a tragedy, because only she knew about her work. She left behind all those unseen images, collecting dust in a tape-bound trunk.

“Don't die with the music still in you,” the motivational speaker Wayne W. Dyer has famously said. You hear that quote a lot in creative circles, where people are urged to express their truth, to write, paint, sculpt and dance. But without society’s support, it’s a hard and lonely road. I think many people die like this, unheard from. The loss is ours.

I loved reading this so much. It's an issue I talk about a lot with my very talented musician friend here, whose day job is coding. (I sent this to them, and they are who I interviewed in my first podcast episode.) My artist son is dealing with the same soul-crushing battle between bringing his joyful brilliance into the light while still needing to make enough to live.

Also, I saw Maier's photography here in Porto several months ago at a temporary exhibit at a museum and was very moved by it, and by the exhibit in general, which was on the intersection of creative expression, madness, and socioeconomic exclusion.

Many of us have had our talents squandered laboring to survive under capitalism, and the world is poorer for it.

https://open.substack.com/pub/jdgoulet/p/a-stream-of-our-own?utm_source=share&utm_medium=android&r=10bxpq

This was such a great blog and I love the voiceover. If you will allow me it would be so cool to add some of your voiceover clips as an audio installation in Chisel Studios!